|

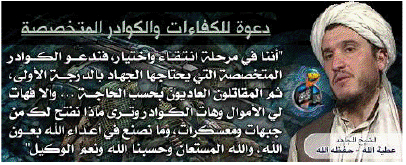

| A banner accompanying an article on Atiyah Abd al Rahman in al Qaeda's "Vanguards of Khorasan" magazine. Image from the SITE Intelligence Group. |

The 21st, and latest, online edition of al Qaeda's "Vanguards of Khorasan" magazine contains a biography of slain al Qaeda leader Atiyah Abd al Rahman. According to a translation provided by the SITE Intelligence Group, the biography is written by a jihadist known as Abu al Bara'a al Kuwaiti. Rahman was killed in a US drone strike in northern Pakistan in August 2011.

Rahman is revered in the biography, which traces his involvement in al Qaeda to the late 1980s after he joined the jihad against the Soviets. The biography continues by noting that Rahman moved with Osama bin Laden to Sudan in the early 1990s, had problematic dealings with the al Qaeda-linked Armed Islamic Group in Algeria (commonly known by the acronym of its French name, "GIA") in the mid-1990s, and was ordered to work with the now-deceased leader of al Qaeda in Iraq, Abu Musab al Zarqawi.

Rahman was not able to join Zarqawi for some unknown reason, according to the al Qaeda biographer. Elsewhere it has been reported that Rahman was tasked with reining in Zarqawi, who had launched a brutal campaign against Shiites and others in Iraq that ultimately tarnished al Qaeda's brand in the eyes of many Iraqis.

Unsurprisingly, "Vanguards of Khorasan" does not mention that Rahman spent much of his terrorist career in Iran.

In July 2011, the US Treasury Department included Rahman on a list of terrorists who worked under an "agreement" between the Iranian government and al Qaeda. At that time, according to Treasury, Rahman was al Qaeda's "overall commander in Pakistan's tribal areas and as of late 2010, the leader of al Qaeda in North and South Waziristan, Pakistan." Previously, Rahman was "appointed by Osama bin Laden to serve as al Qaeda's emissary in Iran, a position which allowed him to travel in and out of Iran with the permission of Iranian officials."

Al Qaeda's biography does say that Rahman returned to Afghanistan at some point after the Taliban fell in late 2001. The biography also hints that al Qaeda maintained safe havens inside Afghanistan even after its ally lost control of the country. "After the blessed September 11th attacks and the move of the mujahideen in the Islamic Emirate to the countries neighboring Afghanistan," SITE's translation of the biography reads, "he returned with his brothers once more to the secure areas in Afghanistan" before unsuccessfully trying to join the jihad in Iraq.

"Engineered" attack on Combat Outpost Chapman

Al Qaeda does not, of course, discuss many of the sensitive operational details of Rahman's career. Rahman served as chief-of-staff to bin Laden prior to the al Qaeda master's demise and was responsible for executing some of al Qaeda's most secretive missions. For example, Rahman was reportedly involved in helping Osama bin Laden plan a possible attack against the US to commemorate the Sept. 11, 2001 attacks. And, declassified documents reveal, Rahman received bin Laden's order to relocate "hundreds" of al Qaeda operatives to the Kunar, Nuristan, Ghazni, and Zabul provinces in Afghanistan in order to escape the drones buzzing above northern Pakistan.

While al Qaeda's biography does not discuss these details, the group does celebrate Rahman's role in the Dec. 30, 2009 attack on Combat Outpost Chapman in Khost, Afghanistan.

On that day, Humam Khalil al Balawi, a Jordanian doctor who the CIA and Jordanian intelligence believed could help locate Ayman al Zawahiri, detonated his suicide vest at the outpost, killing seven CIA officials and security guards as well as a Jordanian intelligence official.

Al Qaeda says that Rahman "engineered" al Balawi's attack. Indeed, Rahman's role in the operation has long been known.

In his book The Triple Agent: The al-Qaeda Mole Who Infiltrated the CIA, the Washington Post's Joby Warrick reports that al Balawi had sent his contact a short video clip of Rahman and other men dressed in Pashtun garb. Unbeknownst to the CIA and the Jordanians at the time, the video was meant to convince al Balawi's handlers that he could deliver top al Qaeda operatives who had been wanted for years. Rahman's "face was instantly recognizable to the agency's counterterrorism experts," Warrick recounts, "even though no American officer had seen the man in eight years."

The bait worked, as al Balawi and Rahman lured the al Qaeda hunters into a trap.

The attack on Outpost Chapman demonstrates the extent to which al Qaeda is tightly integrated with other jihadist groups operating in Pakistan and Afghanistan. While al Balawi was doing Rahman's bidding, he also worked with the Pakistani Taliban, which took credit for the operation.

Al Balawi even appeared in a video with Hakeemullah Mehsud, the leader of the Pakistani Taliban. "We will never forget the blood of our emir Baitullah Mehsud," Balawi said of Hakeemullah's predecessor. Balawi continued, "We will always demand revenge for him inside America and outside. It is an obligation of the emigrants who were welcomed by the emir [Baitullah]."

The Pakistani Taliban claimed that the attack on Chapman was revenge for the killing of Baitullah. And in May 2010, a Pakistani Taliban operative named Faisal Shahzad attempted to detonate a car bomb in New York City's Times Square. Shahzad claimed that his failed attack was revenge for the death of Baitullah, too.

Some US officials have pointed to the successful drone strikes against Rahman and other senior al Qaeda operatives in Pakistan as evidence that the organization's core is on an irreversible path to defeat. There is no doubt that such strikes have weakened al Qaeda. However, al Qaeda was smart enough to forge lasting bonds with other jihadist groups that have an international reach, such as the Pakistani Taliban.